NEW RESEARCH: 5 Takeaways From Data on Teens, Social Media, and Mental Health

What it means, what it doesn't, and what we do about it.

For what it’s worth and for the first time ever, I’ve recorded an audio version of this for those of you who’d prefer to listen than read. Appreciate the mower running in the background—it’s like landscaping ASMR. Let me know if you like audio articles and want more!

Just a couple of weeks ago Pew Research Center published some new data on teens, social media, and mental health. I was asked to comment on it for an article in Baptist Press, and so I thought I’d take a bit more time to unpack some of my thoughts here.

Feels a bit nostalgic to take some space in this newsletter to look at data on social media use and analyze it a bit. Grab some coffee. Get comfy. This is going to be reminiscent of what we used to do around here.

1. Almost half of teens say that social media harms their peers

Almost half of teens say that social media has a “mostly negative” effect on their peers. This is up significantly since teens were asked the same question in 2022. Likewise, the share of teens who believe social media has a “mostly positive” effect on their peers has decreased by more than half in the same time. The share of teens who believe it has a “neither positive nor negative” effect is nearly flat since 2022.

What does this mean? It means that teens are slowly beginning to adopt a more sobered, realistic view of how social media impacts their peers. It is reasonable to think teens have a more negative view of how social media affects their peers than about how social media affects themselves. This would be logical—“Oh yeah, my friends have problems with social media. But me? No way!”—but I’m not sure there is enough data here to suggest one way or the other.

In fact, here’s a sort-of-hilarious, sort-of-sad chart that demonstrates this dissonance:

What does this not mean? It does not mean that teens will be using social media any less than they have before. As I said in the linked Baptist Press article above, “People engage in habits and substances they think are bad for them because they are afraid of what may happen if they stop.” But what about if teens are reporting they are using social media less? Well, we’ll get to that in a couple of points.

2. Teens have confusing views on the ways social media affects them.

This chart is fascinating to me for a handful of reasons, but what I want to dive into here is that 19% of teens say that social media helps their confidence, while only 10% of teens say social media helps their mental health.

Significantly more teens think that social media hurts rather than helps their mental health (19% v. 10%), but the numbers are almost flipped for how it affects confidence (which 19% say social media helps versus 15% say hurts).

One other note: I think it’s fascinating that 30% of teens say that social media helps their friendships. I wonder if this is a misconception among teenagers. I wonder if they see social media as helpful for their friendships because in order to maintain their friendships they must use social media…which doesn’t necessarily mean social media helps their friendships.

Needing social media to keep friendships alive doesn’t mean social media yields healthy friendships. So, in one sense, social media “helps” friendships because teen friendships rely on social media to survive like an opioid addict needs his opioids to be able to function, but that doesn’t mean that social media “helps” friendships by making them any more healthy than they would be without social media. Is the opioid addict really “helped” by the drug as it keeps him functioning, or would he be better without it altogether?

What does this mean? Teens have mixed views, it seems, on how social media affects their inner thought-lives. The same share of teens believe social media hurts their mental health as helps their confidence. Um, what? Unless teens are saying, then, that their chief mental health concern is over-confidence and pride, I’m a bit confused. It is almost as if teens have not yet fully developed their brains and are unable to bear the burden of influence that social media has on their inner thought-life and emotional well-being.

What does this not mean? I think it’s important to not read too much into these particular numbers just because such a high percentage of teens answered “neither helps nor hurts” for all of the different areas in this question.

3. Girls are more negatively affected by social media than boys.

In virtually every category, except “grades” in which boys and girls are equal, teen girls report more negative impacts of social media on their lives than boys do. In some cases, like in the areas of ”mental health” and “confidence,” girls report negative impacts at almost and around twice the rate.

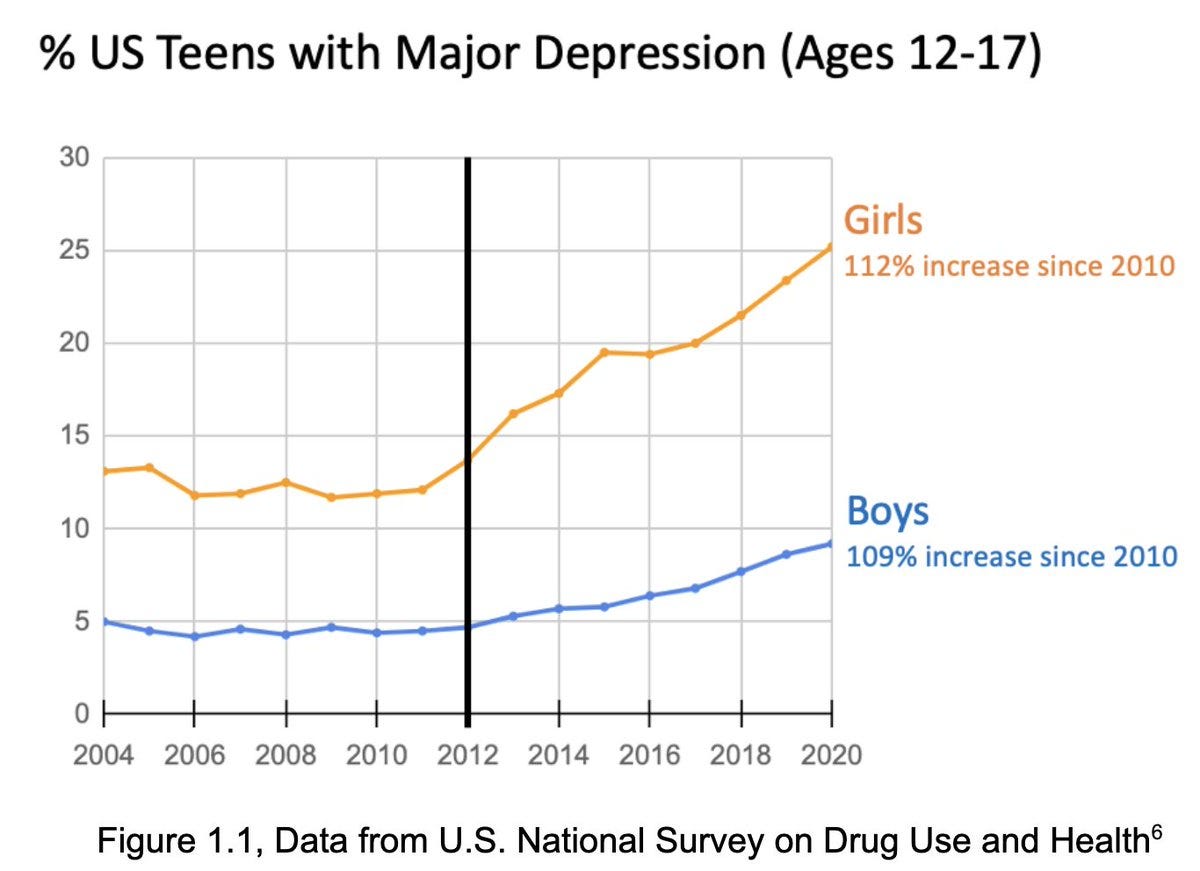

What does this mean? The data continues to prove out what Jonathan Haidt and others have written and spoken about for years: teenage girls are hurt by social media more than teenage boys are. This data is not too dissimilar from data we looked at in this newsletter back in 2022. See this chart Haidt has shared in multiple times and places:

Generally speaking, teenage girls work out conflict socially, whereas teenage boys work out conflict physically. Therefore, it follows that as teen girls workout conflict socially in ways that are supercharged by social media, they are more likely to feel the negative impacts of its use than boys, who are not going to be driven to fight any more because of their use of social media.

Snapchat and Instagram make it easier for girls to backstab and triangulate, but they do not make it easier or more appealing for boys to punch each other.

What does this not mean? I don’t feel I need to state the obvious here, but lacking anything else more constructive, I will. This data does not mean that teen girls are weaker or in any other way lesser than teen boys. If anything, this data tells us that teen girls are more socially aware and emotionally attuned than boys—as anyone who has spent time with teenage boys could tell you from experience—and, thus, they are more dramatically affected by the negative ways that social media impacts social interactions and mental health.

4. Teens’ experiences on social media are truly a mixed bag.

I don’t need to hash out all of the data points here, but I think the chart is clear: teens’ experiences on social media are not overwhelmingly awesome or awful. This is an important point to note, I think.

Often when I have spoken at churches, to parent groups, on podcasts, and the like, it seems that many tend to think that one’s view on social media has to be binary—either you think social media is 100% awful all the time or you think social media is 100% awesome all the time. We do this, I think, because it’s easier to think in absolutes than it is in nuance. (Psst—this is a negative side effect of social media use!)

I talk about this a lot because while I have written two books about the dangers/problems with social media, I also work in digital media and help Christians use digital media more effectively. Some see these two realities as in conflict with one another, and I don’t think that has to be the case.

What does this mean? Social media is not always awful, and it is certainly not always awesome. I wrote two books about the problems with social media and not about the amazing bits of social media because I think we’re well-attuned to the pros of social media and not aware enough of the cons of social media. All of this is to say: social media use can be constructive and destructive at the same time—even if it is bent toward destruction more than construction—and this data about teens’ social media use bears that out.

What does this not mean? It does not mean that social media is a mixed bag for all teens. Surely some teens have a mostly positive experience with social media. Some teens have a mostly negative experience with social media. And some do experience the good and the bad all at once. If you find yourself parenting or overseeing teenagers in some way, don’t assume their relationship with social media is so binary—all bad or all good. Recognize that they may love how social media helps them connect with people who share their interests around the world, but simultaneously detest how it makes them feel about their bodies.

5. Teens say they use social media less…but do they really?

So first, we have this chart:

“Wow!” You may be tempted to think, “Look at how many teens are cutting back on their smartphone and social media use! Sure, more people haven’t cut back on time than have, but those numbers are closer than I would have expected!”

Oh sweet, summer child. Let me introduce you to the dastardly concept of social desirability bias in behavioral health research.

The National Institutes of Health described it in this way from an article in 2016:

When researchers use a survey, questionnaire, or interview to collect data, in practice, the questions asked may concern private or sensitive topics, such as self-report of dietary intake, drug use, income, and violence. Thus, self-reporting data can be affected by an external bias caused by social desirability or approval, especially in cases where anonymity and confidentiality cannot be guaranteed at the time of data collection. For instance, when determining drug usage among a sample of individuals, the results could underestimate the exact usage. The bias in this case can be referred to as social desirability bias.

I think it is fair to say that excess social media and phone use is so common and yet so socially taboo in our culture that the risk of social desirability bias is incredibly high even if in a rather innocuous and confidential study like this one conducted by Pew.

Pew reported that these numbers demonstrate a slight increase from when the question was asked in 2023, which is encouraging, but I think the social taboo of being “too online” has only increased since then, so it would follow that the risk of social desirability bias would as well.

How do we know that the social taboo of spending too much time on social media has continued to grow? Look at this graph here:

Now, don’t hear me saying this chart is evidence that the “too online” taboo is growing. It is not evidence of that. But, taken together, these two charts tell us: more teens than ever are self-reporting that they are spending less time on their phones and social media, but more teens than ever are self-reporting that they are spending too much time on social media.

Of course, both things can be true! Let’s be clear: any given teen could simultaneously say, “I am spending less time on my phone and on social media, but it’s still far too much.” That is a very real outcome in a survey like this.

But let’s use our brains for a second.

An intimate understanding of and appreciation for social desirability bias would lead us, I think rightly, to recognize that what we probably have here is teens answering these survey questions they way they think they should rather than in a way that reflects reality.

In short, I’d love to see the screen time reports of the teens who answered this survey. Only then would we have any real idea of whether or not they’re telling the truth, because this data smells funny to me. But hey, I’m just a dad with a newsletter, not a social scientist.

What does this mean? Since I’ve already elaborated on these charts a good bit, I’ll keep these two sections a bit short. What does this mean? Taken at face value, it means that teens are developing a healthier relationship with their phones and social media, perhaps using it less despite feeling like they’re using it too much. Thinking about it more critically, it at least means that teens know the “right answers” when it comes to answering a survey question like this, regardless of what their weekly screen time reports would actually tell us in reality.

What does this not mean? I suppose the cat’s out of the bag here because of my mini-rant above, but to reiterate, what this data does not mean is that teens are using social media and their smartphones less than they have before. I think these data points should be taken with a massive amount of skepticism, not because the fine folks at Pew don’t know what they’re doing, but because self-reported social media use data should always yield some suspicion.

So What Do We Do With This Data?

I’m going to be brief here, because I don’t know where all of you are and what responsibility you have to lead and disciple teenagers. Also, I am not yet a parent of teens, and even if I have spent well over a decade in student ministry, parenting teens in a social media world is an experience I feel a bit ill-equipped to address. But I do want to provide just a few thoughts in the way of application as we look at this data, however it is you care and shepherd teens.

First, don’t draw any definitive conclusions from this data for your child or the teens you disciple. The ways that 1,391 teens answered a survey over about a month last fall do not necessarily reflect your specific teen’s relationship with social media. Data like this can be helpful to understand the social ecosystem in which your teen swims and operates with his or her peers, but be careful to not start thinking thoughts about the teens in your care that may not necessarily be true of them despite what the data shows.

Second, consider asking your teen some of the questions from this survey. One way to use this survey in a constructive way in your specific context would be to put some of these questions to your kids or the teens in your student ministry. Instead of wondering how your teens would have answered the Pew survey, conduct a miniature version of the survey in your own home or ministry. And when you ask them about if they’ve been using social media less, you could check their answers to their screen time trackers! ;-)

Third, recognize that your teen’s relationship with social media is likely complicated. Double-clicking on one of the points above, I think it’s really important that we recognize that our relationships with social media are complicated—whether we’re teens or not, really. Your teen may be complaining about social media over breakfast one morning while endlessly scrolling TikTok in the evening. This is just real life. We can struggle with social media while also finding parts of it worthwhile. These things are not binary, and that’s okay. It just requires us to think a bit harder and use some more discernment when we engage.

Finally, use data like this and articles like mine to have ongoing conversations with your teen about his or her relationship with social media. When I have met with parents and student ministry leaders over the years, the biggest issue I’ve recognized is that people simply aren’t talking about social media enough. There could be lots of reasons for this—passivity, shame among parents about their own social media issues, etc.—but the silence about social media is widespread. If you want to broach the potentially-touchy subject of social media with the teens in your home or ministry, use this data or articles like mine to do it! Ask what your teen thinks. Lead with humility, not accusations of misuse.

Social media continues to be the most widespread and influential discipleship force in the world, foremost in the lives of our teenagers. Their relationships with and perspectives on social media are complex. But that’s okay. Let’s avoid frustration and pursue clarity. That starts with open and regular communication.

Thanks for reading. Felt nice to dip back into these waters a bit. Until next time.

-Chris

Yes, it was helpful to listen, Chris, and I plan to read the charts too.