Ukrainians Aren’t Dancing on TikTok

No one's going viral in Sudan.

Russia invaded Ukraine about 15 months ago now, which is crazy to think about, especially when most people thought Kyiv would fall to Russian soldiers within the first week of the conflict.

It feels like the eyes of the world are watching Ukrainians fight for not just their freedom, but for the future of freedom for all sovereign nations to maintain their sovereignty. The thought seems to be, “If Russia can just invade Ukraine, why can’t __________ just invade ___________?” Some fear that China will pull a similar move with Taiwan before the year is out.

The war in and for Ukraine certainly feels like more than just a war for the land and people of Ukraine.

While we’re considering world crises, we can’t ignore the ongoing conflict in Sudan between the army and a paramilitary force. That conflict has led to the death of hundreds and displacement of thousands.

But throughout the rest of the world, especially in the developed West, we continue about our lives. We watch our favorite sports teams, we work our jobs, we attend our churches, and we continue to create and consume social media content.

The Unreality of Social Media Trends

I like to keep track of trends on social media. It has always been fascinating to me to see what’s popping on different corners of the social internet and what that tells us about our current cultural moment (at least with regard to internet culture). I often ask questions like:

What are the current YouTube thumbnail trends and how have they changed?

What songs are trending as popular sounds on TikTok as audio memes and why?

What are some of the fastest-growing subreddits on Reddit and what does it mean?

Why does anyone continue to use Instagram reels?1

Recently as I was going through some of the trends I’ve been tracking on YouTube and TikTok in particular it struck me how many of the most notable trends in social media are set and maintained by people in developed, wealthy, peaceful countries—namely, the West. Of course there are popular TikTokers and YouTubers who aren’t from the West, but they seem to be more of the exception than the rule.

And that’s when the thought struck me. No one is dancing on TikTok in Ukraine. No one’s going viral in Sudan.

No one dances on TikTok when their life is in danger. The homeless and hungry aren’t the ones complaining about trans people being on beer cans. Social media trends and viral content are the fruit of affluence and luxury.

I can’t speak for you, of course, but I can speak for myself and what I observe in the broader internet: I think we often forget that what floats to the top of social media is preternaturally rooted in worlds of peace and wealth and at odds with so much of reality.

This isn’t to say you don’t see images of war or clips of mass shootings on social media, because if spend any measurable time on certain platforms, you do. But by-and-large, the content that fills our feeds and our brains is borne out of cultures of comfort and ease. What does this mean? I think it means a lot, but I just want to highlight one implication.

A Warped Hierarchy of Needs

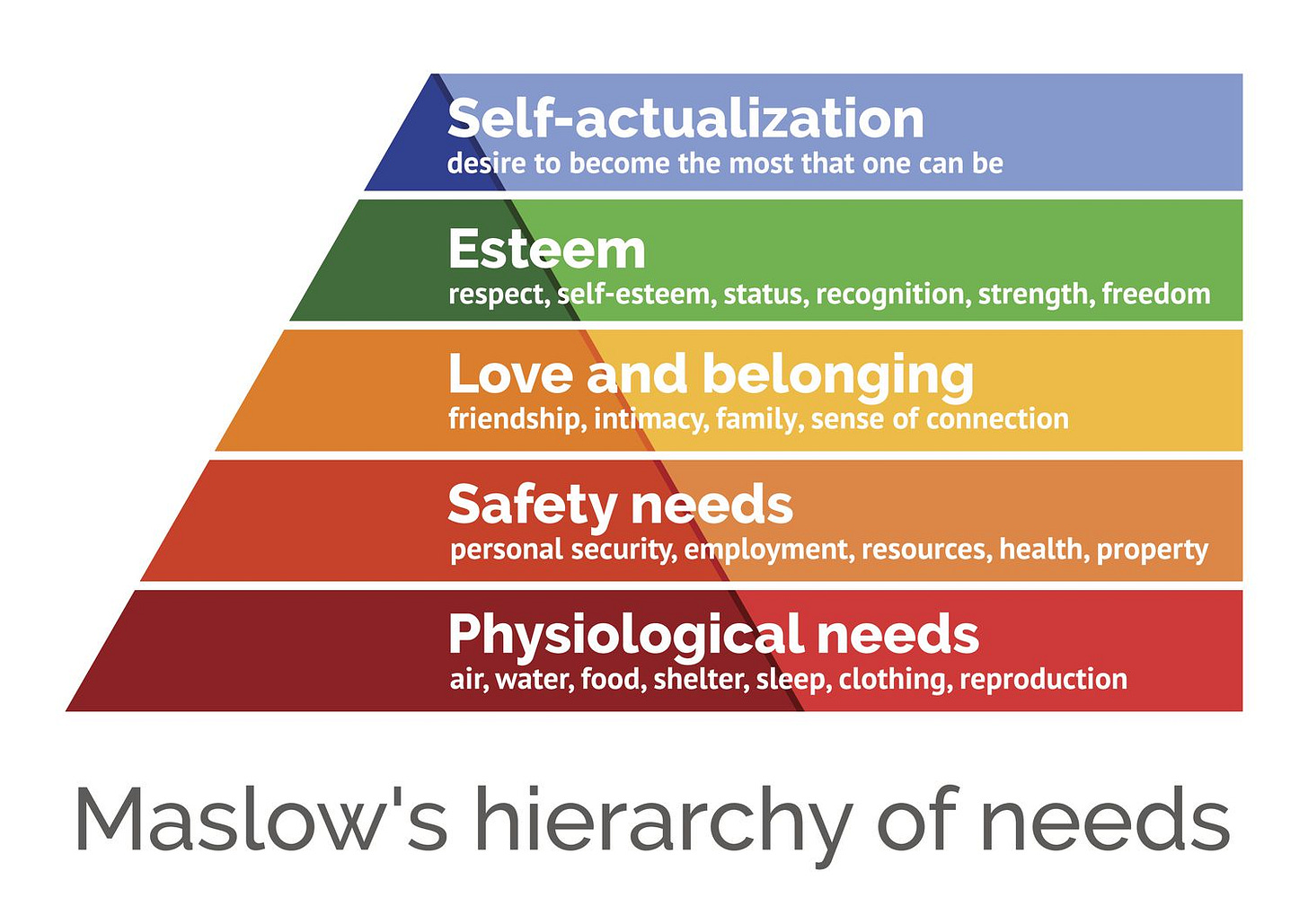

I first came across Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in college, but I didn’t really think about it much until a few years ago. American psychologist Abraham Maslow developed his Hierarchy of Needs to explain why people act the way they do.

Of course the hierarchy isn’t perfect, but it’s helped me navigate a lot of interpersonal obstacles over the years, and I think there’s a lot we can learn when we take a moment to realize what motivates people and how people act when their basic needs aren’t met (or when they are perceived to not be met).

This is why it matters that the most popular social media content and the loudest voices are borne out of cultures of comfort and relative ease: when the loudest people on the internet are not starving or in danger of being killed, the issues that get the most attention are often the things that matter the least in the grand scheme of things, even if they matter a lot to the people posting about them.

What happens, then, when you scale this up to millions of people posting lifetimes of content on social media every single day is that you can be easily tricked into thinking that these most trendy and viral concerns are the most important concerns.

Meanwhile, the people who are starving or are worried about being killed don’t have the means to post about their problems, so their problems are simply ignored.

When you are chronically online, it’s like the bottom two levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy are just chopped off—you never see content about life or death matters, you just see viral tweets about pronouns or trendy TikToks about how awful it is to have to sit in Zoom meetings all day.

This isn’t to say that important issues cannot be addressed on social media—they certainly can be. Matters of racism, sexual abuse, and otherwise have had light shined on them because of social media in the last decade, and that’s good. But those issues are sort of exceptional—most of us would admit that the vast majority of grievances we witness online are not of such import.

Our relationship with the social internet warps our minds into thinking that whatever issues go viral or whichever users are loudest are of utmost importance. This simply isn’t the case. The tunnel vision caused by our feeds leads us to care more about frivolities than we ought and completely ignore matters of greater importance because we simply forget they exist.

The problems that get the most attention on social media are rarely existential because the people dealing with existential problems are too busy trying to keep existing to complain on the internet.

This should shape our perspective on the kinds of things we see people complain or fight about online.

Ukrainians aren’t dancing on TikTok.

No one’s going viral in Sudan.

But did you hear all the talk

About the dude on the beer can?

This one is a joke, but only kinda.

We Hokkiens have a saying, "When your stomach is full, you get too free."

Meaning, when the majority of you time is not spent trying to feed yourself, you will end up with too much times on your hands and that usually means there will be time for mischief.

Wow, this was incredibly insightful and creative all at the same time. Thanks for sharing, Chris. I try to have this conversation with people often and this is a really succinct way to put it. Never thought about it in terms of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.